In this post, notes of Unit 1 (Ancient Delhi and adjoining sites – Mehrauli Iron Pillar) from GE-1: (Delhi through Ages) are given which is helpful for the students doing graduation this year.

Introduction to the Mehrauli Iron Pillar

A. Basic Identification and Location

Current location: Qutub Minar Complex, Mehrauli, Delhi.

The Mehrauli Iron Pillar stands today in the courtyard of the Quwwat-ul-Islam Mosque, at the heart of the Qutub Minar Complex in South Delhi. It is one of the most prominent attractions within the complex, positioned directly opposite the mosque’s prayer hall.

It is important to note that the pillar was not built by the rulers who constructed the Qutub Minar or the mosque. Instead, it was already an ancient, revered object when the complex was built in the late 12th and early 13th centuries.

The Islamic builders consciously chose to incorporate this pre-existing symbol of power and engineering into their new architectural landscape, thereby legitimizing their own rule by associating it with a legacy of imperial authority.

Original location debate: Udayagiri (Vidisha, M.P.) vs. Mehrauli.

There is a significant historical debate about where the pillar was originally erected.

The Udayagiri Theory: This is the most widely accepted theory among historians. It suggests that the pillar was originally located in the ancient temple complex of Udayagiri, near Vidisha in modern-day Madhya Pradesh.

Udayagiri was a major site of astronomical, religious, and political significance during the Gupta period, closely associated with King Chandragupta II, who is named in the inscription.

The theory posits that the pillar was a dhvaja-stambha (a flagstaff or standard of victory) dedicated to the god Vishnu, erected in front of a temple.

It is believed to have been moved to Delhi centuries later, possibly by the Tomar or Chauhan Rajput kings who ruled from Delhi, to adorn their own capital city.

The Mehrauli Theory: A less common theory argues that the pillar has always been in Mehrauli.

Proponents suggest that the area around Mehrauli, known in ancient times as Dhillika, was an important political and cultural center.

They argue that the pillar might have been part of a large Vishnu temple complex or even a massive astronomical instrument (as the name “Dhillika” is linked to an iron nail used in astronomical devices).

However, the lack of archaeological evidence for a large Gupta-era complex in Mehrauli makes this theory less convincing to most scholars.

In summary, while its current home is definitively the Qutub Complex, the evidence strongly leans towards Udayagiri being its original birthplace.

B. Significance of Delhi’s Iron Pillar as a Historical Source

The Mehrauli Iron Pillar is far more than just an old iron object; it is a multi-dimensional historical source that offers invaluable insights into ancient India.

Epigraphic source: Inscriptions in Sanskrit.

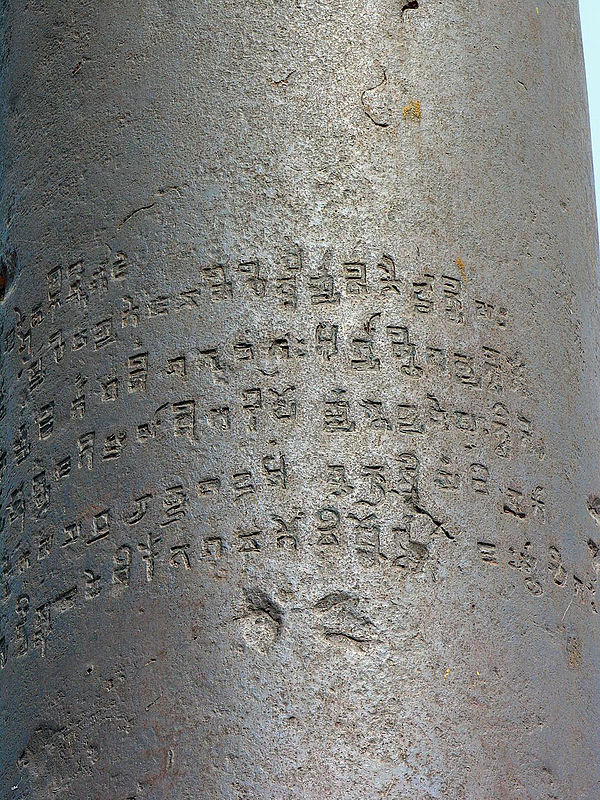

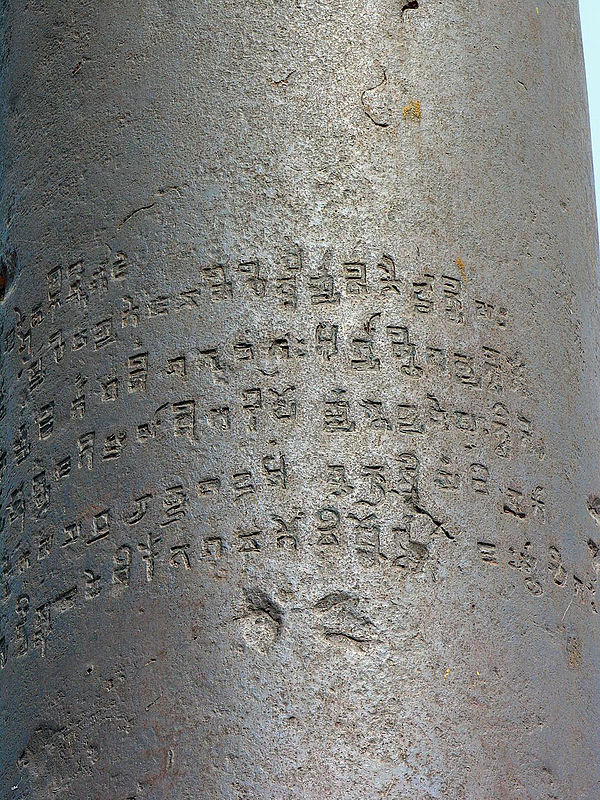

The pillar bears a six-line Sanskrit inscription in a script called Brahmi, specifically the style used during the Gupta era.

This inscription is a primary source document—a direct message from the past. It is composed in a poetic meter and reveals crucial information:

It glorifies a king named “Chandra,” who is almost universally identified as the mighty Gupta emperor Chandragupta II Vikramaditya (c. 375–415 CE). This directly links the pillar to the “Golden Age” of ancient India.

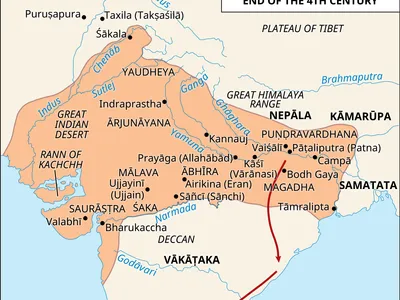

It describes his military conquests, mentioning him crossing the “seven mouths of the Sindhu (Indus) river” and defeating a people called the Vahlikas. This provides geographical and political details about the extent of his empire.

It dedicates the pillar to the Hindu god Vishnu, stating it was erected on “Vishnupada hill” (which supports the Udayagiri theory, as the site has Vishnu associations). This offers a glimpse into the religious patronage of the Gupta kings.

Essentially, the inscription is a proud royal press release carved in metal for eternity.

Metallurgical marvel: Testament to ancient Indian iron-working skills.

This is the pillar’s most famous attribute. Standing over 7 meters tall and weighing more than 6 tonnes, it is a breathtaking feat of engineering that has fascinated scientists worldwide.

Its most famous quality is its rust resistance. Contrary to popular belief, it is not made of “stainless steel.” For over 1600 years, it has withstood sun, rain, and wind with only a thin, stable layer of oxidation protecting it, while modern iron structures rust away in decades.

The secret lies in its unique composition and forging process. Ancient Indian ironsmiths used exceptionally pure wrought iron with a high phosphorus content and very low Sulphur and manganese. When forged, this combination led to the formation of a thin, protective film called “misawite” that acts as a barrier against moisture and oxygen.

This knowledge wasn’t accidental; it demonstrates a highly sophisticated and deliberate understanding of metallurgy, making the pillar a silent testament to the advanced scientific and technological prowess of ancient India.

Symbol of political authority and imperial legacy.

The pillar was never just a piece of metal; it was a powerful political symbol.

In its original context, it was a victory pillar (jayastambha). By erecting it, Chandragupta II was not just honoring a god but also proclaiming his military might, territorial conquests, and unchallenged authority to his subjects and rivals. It was a permanent, unmissable statement of imperial power.

Its later placement in the Qutub Complex shows how this symbolism was recognized and repurposed. The new Sultans of Delhi, by incorporating this ancient symbol of Hindu kingship into the very fabric of their first major mosque, were making a powerful statement: they were the new rulers, inheriting the land and the legacy of the past emperors. It was a deliberate act to ground their new authority in the region’s long history of power.

Thus, the Mehrauli Iron Pillar serves as a unique bridge connecting the Gupta Empire to the Delhi Sultanate, embodying the continuous flow of history and the enduring nature of symbolic power.

Historical Context and Origin

A. The Gupta Empire: The Probable Provenance

The Gupta period as a “Golden Age” of art, science, and literature.

The Gupta Empire (c. 3rd to 6th century CE) is often called the “Golden Age” or “Classical Age” of ancient India. This was a period of extraordinary peace, prosperity, and flourishing creativity. Under stable and powerful rulers, India witnessed:

Artistic Brilliance: The creation of sublime sculptures and magnificent temple architecture, such as the Dashavatara Temple at Deogarh. The Ajanta and Ellora caves feature some of their most exquisite paintings, showcasing a mastery of form, color, and expression.

Scientific Pioneering: Great minds like Aryabhata and Varahamihira made groundbreaking discoveries. Aryabhata proposed that the Earth rotates on its axis and revolves around the sun, calculated the value of pi (π), and made immense contributions to mathematics and astronomy.

Literary Excellence: Sanskrit literature reached its peak. Kalidasa, often regarded as India’s greatest poet and playwright, composed timeless works like Abhijnanashakuntalam (The Recognition of Shakuntala) and Meghaduta (The Cloud Messenger).

The Mehrauli Iron Pillar is a product of this enlightened era. It wasn’t created in isolation but was a part of this cultural ecosystem that valued knowledge, skill, and grandeur.

Patronage of technological and metallurgical advancements.

The Guptas were not just patrons of art; they were also great supporters of science and technology. The pillar is the finest example of this. Creating such a massive, single piece of wrought iron required:

Advanced Smelting: The ability to smelt iron ore at very high temperatures to produce a large quantity of high-purity metal.

Sophisticated Forging: Techniques to skillfully hammer and weld large masses of hot iron into a single, cohesive pillar. This was a monumental blacksmithing achievement.

Metallurgical Knowledge: As proven by its rust resistance, the ironsmiths possessed deep, likely empirical, knowledge of how phosphorus and other impurities affect the properties of iron.

This level of craftsmanship suggests the existence of state-supported guilds or workshops where such advanced technical knowledge was developed and preserved, all under the patronage of the Gupta emperors.

B. The Inscription: Deciphering the Key

The inscription on the pillar is like a time capsule, offering direct evidence from the past.

Language: Sanskrit.

The language used is Sanskrit, the classical and scholarly language of ancient India. This was the language of court, literature, and religion, indicating that the message was intended for an educated and elite audience, reinforcing the pillar’s official and royal status.

Script: Late Brahmi (or Gupta Brahmi).

The script is a beautiful and precise form of the Brahmi script, specifically the variety used during the Gupta period. The letters are well-formed and graceful, often described as “classic” or “monumental.” Epigraphers (scholars who study inscriptions) can date the pillar to the Gupta era primarily based on the distinct style of this script.

Content Analysis:

The inscription is a short but powerful poem in the Anushtubh (Shloka) meter.

a. Dedication to the Hindu god Vishnu: The inscription begins by stating that the pillar was erected on a hill named “Vishnupada” (the hill of Vishnu’s feet). It is dedicated to the god Vishnu, establishing it as a deeply religious object, likely a dhvaja-stambha (flagstaff) in front of a Vishnu temple.

b. Praise of a king named “Chandra”: The central figure celebrated is a powerful king referred to simply as “Chandra.” Based on the description of his military campaigns and the paleography (style of writing), historians have conclusively identified “Chandra” as Chandragupta II Vikramaditya (c. 375–415 CE), one of the greatest Gupta emperors. The name “Vikramaditya” means “Sun of Valour.”

c. Description of the king’s military conquests: The poet boasts of King Chandra’s unparalleled military achievements. Two key victories are mentioned:

He is praised for having “crossed the seven mouths of the Sindhu (Indus river)” and defeated the Vahlikas. This likely refers to his conquests in the northwestern regions of the Indian subcontinent.

He is also described as having won the “supreme sovereignity of the earth by his own valour.” This is typical of the grand, poetic style used to glorify a king’s digvijaya (conquest of the directions).

In essence, the inscription merges the divine and the royal, portraying Chandragupta II as a divinely favoured conqueror.

C. Debate on Original Location and Purpose

Theory 1: Erected at Vishnupada (Udayagiri) as a standard of Vishnu.

This is the most strongly supported theory. The inscription itself states it was erected on “Vishnupada hill.” Udayagiri, near Vidisha (Madhya Pradesh), is a site replete with Gupta-era rock-cut caves and sculptures dedicated to Vishnu. It was a major political and religious center for Chandragupta II and his minister, Virasena. Many scholars argue that the pillar originally stood here as a victory monument and standard of Vishnu, celebrating the king’s western conquests. It was likely moved to Delhi centuries later.

Theory 2: Always associated with Delhi, possibly as an astronomical instrument.

A less accepted theory suggests the pillar has always been in the Mehrauli area. Proponents argue that the region, known in ancient times as Dhillika, might have been a significant center. Some have speculated that the pillar could have been part of a large astronomical device (as the name “Dhillika” is sometimes linked to an iron nail used in such instruments). However, the lack of any archaeological evidence for a large Gupta-period complex in Mehrauli makes this theory difficult to prove.

How and when it was moved to its current location (possibly by the Tomars or Chauhans of Delhi).

The most plausible explanation is that the pillar was transported to Delhi between the 10th and 12th centuries CE.

The Tomara Rajputs were the first to build a fortified city called Lal Kot in the Mehrauli area, establishing Delhi as their capital.

They were succeeded by the Chauhan Rajputs.

It is believed that one of these dynasties, seeking to glorify their new capital and connect their rule to the legendary glory of the Guptas, had the pillar moved from Udayagiri to Mehrauli. They would have erected it within their own complex of temples and palaces. Centuries later, when the Qutub Complex was built, the pillar was left standing, incorporated into the new Islamic architecture as a symbol of conquered power.

The Metallurgical Marvel: Scientific and Technological Aspects

A. Physical Specifications and Composition of Iron Pillar

Height, weight, and dimensions.

The Mehrauli Iron Pillar is a colossal testament to ancient engineering. Its physical stats are impressive:

Total Height: Approximately 7.21 meters (23 feet 8 inches) above the ground.

Weight: Estimated to be over 6.5 tonnes (about 6,500 kilograms).

Diameter: It tapers from the bottom to the top. The diameter is 41.6 cm (16.4 inches) at the bottom and 29.5 cm (11.6 inches) at the top, just below the ornate bell capital.

Underground Part: A portion of the pillar is buried below the present floor level. Its total original length is believed to be closer to 12-13 meters if the buried section is included.

These dimensions highlight the monumental scale of the project. Forging a single piece of wrought iron of this size over 1,600 years ago was an unparalleled feat of blacksmithing.

Chemical composition: High phosphorus, low sulphur/manganese content.

Modern scientific analysis has revealed the pillar’s unique recipe, which is the secret to its longevity. Its composition is strikingly different from modern iron:

High Phosphorus (P): The pillar has a very high phosphorus content (0.25% – 1%), which is a key factor in its rust resistance. In modern steel-making, phosphorus is considered an impurity as it makes steel brittle. However, in this context, it played a crucial positive role.

Low Sulphur (S) and Manganese (Mn): The sulphur content is very low (<0.005%), and manganese is almost absent. This indicates the use of high-quality iron ore and a highly efficient smelting process, as sulphur promotes brittleness and corrosion.

This specific chemical signature is a result of the unique iron ore and the ancient smelting technique using charcoal (instead of coke), which doesn’t introduce sulphur into the metal.

B. The Enigma of Rust Resistance

The common misconception of being “stainless.”

A popular myth claims that the pillar is made of a “stainless” or “non-rusting” metal that modern science cannot replicate. This is incorrect. The pillar is not stainless; it is made of wrought iron, which is highly susceptible to rust. If placed in a humid, marine environment like Mumbai or Kolkata, it would have corroded away centuries ago. Its survival is due to a combination of its unique composition, the skill of its creators, and its specific environment.

Scientific explanation: Formation of a protective passive layer (misawite).

The pillar’s resistance is due to the formation of a thin, protective film called a “passive layer.” This layer, only a few hundred microns thick, acts as a shield, preventing moisture and oxygen from reaching the pure iron underneath and starting the rusting process. This layer is primarily composed of misawite (δ-FeOOH), a compound that is stable and non-porous.

The formation of this layer is due to three interlinked factors:

a. Role of high phosphorus content: This is the most critical factor. The high phosphorus content in the iron allows for the formation of a phosphate-rich film at the metal-air interface. This film is a key component of the stable passive layer (misawite). It acts as a catalyst that promotes the formation of this protective shield and makes it more durable.

b. Role of slag particles in the iron: Ancient Indian iron was not pure in the modern sense. It contained tiny particles of slag (iron silicate glass) interspersed throughout the metal matrix. These particles, a byproduct of the smelting process, actually help in forming a more continuous and adherent protective layer. They make the passive layer uneven and dense, further hindering the penetration of corrosive agents.

c. The dry, alkaline atmosphere of Delhi: The environment plays a crucial role. Delhi has a relatively dry climate for most of the year. More importantly, the soil and atmosphere around the pillar are slightly alkaline. This alkaline environment is essential for the stability of the misawite passive layer. If the environment were acidic (e.g., in an industrial area with acid rain), the protective layer would break down, and the pillar would begin to rust actively.

In simple terms, the ancient ironsmiths, without knowing the modern chemistry, created a metal whose properties, when combined with Delhi’s climate, result in a self-protecting shield.

C. Ancient Indian Iron-Working Techniques

The Wootz Steel and Delhi Iron: A comparative context.

Ancient India was famous for two legendary ferrous metals:

Wootz Steel: This was a high-carbon steel, famous for producing “Damascus swords” known for their sharpness, strength, and distinctive wavy pattern. It was made by melting wrought iron with charcoal in a closed crucible.

Delhi Iron (of the Pillar): This is a low-carbon wrought iron. The goal here was not to create a hard, sharp weapon but a massive, durable, and forgeable structure. The technology focused on smelting and forging at lower temperatures to create a large, cohesive mass of metal without welding flaws.

Both technologies demonstrate a sophisticated, but different, mastery over iron.

Forging methodology: Hammer-welding of large wrought iron pieces.

The pillar was not cast like a modern statue. It was hand-forged by a process called hammer-welding.

1. Smelting: Iron ore was smelted with charcoal in small furnaces to produce individual lumps of pure iron called “blooms.”

2. Heating and Hammering: These hot blooms were repeatedly hammered to squeeze out the molten slag and weld them into a single, solid mass.

3. Building the Pillar: To create a pillar of this size, ironsmiths would have heated and hammer-welded hundreds of these smaller iron pieces together into a massive cylindrical form. This required incredible skill to ensure every weld was perfect; a single flaw could have led to the pillar cracking under its own weight over time.

Reflection of advanced knowledge in smelting and forging.

The creation of the pillar reflects a system of advanced, codified knowledge:

Empirical Metallurgy: The smiths had an empirical (experience-based) understanding of how different ores, fuels, and forging techniques affected the final product’s properties.

Organized Production: Creating such a massive object required a coordinated effort of miners, smelters, blacksmiths, and engineers, suggesting the existence of organized guilds supported by royal patronage.

Quality Control: The consistent quality of the metal throughout the pillar’s massive volume shows an exceptional level of process control, achieved centuries before modern metallurgy was born.

The Mehrauli Iron Pillar is not a lucky accident; it is the deliberate and masterful product of a highly advanced technological tradition.

Inscription: A Detailed Epigraphic Analysis

A. Text of the Inscription (Transliteration and Translation)

The inscription is a six-line poem in Sanskrit, carved in a beautiful Brahmi script. While a precise transliteration requires knowledge of Sanskrit diacritics, a commonly accepted translation of its essence is as follows:

> “[He] on whose arm fame was inscribed by the sword, when in battle in the Vanga countries (Bengal), he kneaded (and turned) back with (his) breast the enemies who, uniting together, came against him;

> He, by the breezes of whose prowess the Southern Ocean is even still perfumed;

> He, the remnant of whose great zeal, who, having destroyed the Vahlikas, had crossed the seven mouths of the river Sindhu (Indus) and conquered the Vahlikas;

> He, of great glory, who, having the name of Chandra, carried a beauty of countenance like (the beauty of) the full moon, having in faith fixed his mind upon (the god) Vishnu, this lofty standard of the divine Vishnu was set up on the hill (called) Vishnupada.”

In Simple Terms: The inscription poetically states that a king named Chandra, who possessed immense military power (he defeated Bengalis in the east, perfumed the Southern Ocean with his fame, and crushed the Vahlikas in the northwest), erected this lofty pillar as a standard of the god Vishnu on the Vishnupada hill.

B. Literary and Poetic Merit

The inscription is not a simple factual record; it is a finely crafted piece of poetry designed to glorify the king.

Use of the Anushtubh (Sloka) metre.

The entire inscription is composed in the Anushtubh metre (also known as Shloka). This is the most common and popular metre in classical Sanskrit poetry, used in epic texts like the Mahabharata and Ramayana.

It consists of four quarters (or lines) of eight syllables each.

It has a specific rhythmic pattern that makes it harmonious and easy to recite and remember.

The use of this familiar and respected metre elevates the inscription from a mere notice to a lasting literary composition, ensuring its message was delivered with dignity and gravitas.

Poetic imagery and grandiloquent style.

The composer used powerful poetic devices and a grand, boastful style (atiśayokti) to create a larger-than-life image of the king:

Hyperbole (Exaggeration for effect): The line “by the breezes of whose prowess the Southern Ocean is even still perfumed” is a masterful metaphor. It suggests the king’s fame and power are so vast and enduring that they have physically altered the environment, scenting the ocean winds themselves.

Visual Imagery: Comparing the king’s face to the “beauty of the full moon” (purnachandra) is a classic Sanskrit trope to signify ideal beauty, radiance, and calm majesty.

Complex Syntax: The inscription is a single, long, complex sentence that builds up the king’s attributes one after another, creating a sense of overwhelming power and achievement before finally revealing the purpose of the pillar.

This style was intentional. It was meant to inspire awe and reinforce the king’s supreme authority and divine connection.

C. Historical Information Derived

Despite its poetic nature, the inscription is a invaluable primary source for historians.

Political ideology: The king as a devotee and conqueror (Digvijaya).

The pillar perfectly encapsulates the ideal of the Gupta king, who was both a chakravartin (universal ruler) and a bhakta (devotee).

Conqueror (Digvijaya): The king’s primary duty was to conquer the “four directions” (digvijaya). The inscription meticulously lists conquests in the east (Vanga), the south (reaching the ocean), and the northwest (Vahlikas), presenting King Chandra as a supreme conqueror.

Devotee: The king is not portrayed as a god himself, but as a devotee who derives his power and legitimacy from Vishnu. The pillar is not a self-glorifying statue of the king; it is a “standard of Vishnu” erected by the king. This establishes a divine contract: the king wins victories because of his devotion, and in return, he offers praise and magnificent gifts to the god.

This combination of military power and religious duty was the cornerstone of Gupta political ideology.

Geographical extent of Chandragupta II’s reign.

The inscription provides crucial clues about the reach of Chandragupta II’s empire:

The East (Vanga): Confirms control or influence over parts of Bengal.

The South: The mention of the “southern ocean” (likely the Indian Ocean near the Bay of Bengal) suggests successful campaigns deep into the Deccan peninsula, possibly against the Vakataka or other contemporary dynasties.

The Northwest (Vahlika): The conquest of the Vahlikas (identified with the Balkh region in Central Asia, Bactria) and crossing the “seven mouths of the Sindhu” (Indus delta) is the most significant claim. It points to Gupta expansion into the traditional domains of the Western Kshatrapas, a major achievement that would have brought immense wealth and prestige.

This paints a picture of an empire of vast proportions, stretching from the Bay of Bengal to the Arabian Sea.

Religious patronage during the Gupta era.

The primary purpose of the pillar, as stated, is religious. It tells us that:

Vaishnavism was prominent: The Gupta kings, while tolerant of all faiths, were particularly devoted to Vishnu. Erecting such a permanent and expensive monument was a supreme act of religious patronage (danam).

Temple Culture: The phrase “standard of Vishnu” implies it was placed before a temple. This suggests the existence of substantial structural temples (likely of stone or brick) during the Gupta period, patronized by the emperor. It reinforces the idea that the Guptas were not just political rulers but also the chief patrons of art, architecture, and religion.

Cultural, Religious, and Political Symbolism

A. As a Dhvaja-Stambha (Flag/Standard Pillar)

In its original context, the pillar was far more than a metal object; it was a powerful sacred and political symbol known as a dhvaja-stambha.

Association with Vaishnavism.

A dhvaja-stambha is a flagstaff that is erected in front of the main deity in a Hindu temple, specifically within the Vaishnava tradition. It symbolizes the presence of the divine and acts as a beacon for devotees.

The inscription explicitly states that the pillar was dedicated to Vishnu and erected on “Vishnupada hill.”

It would have been adorned with a flag (dhvaja) featuring the emblem of Vishnu (like Garuda, the eagle mount). The act of raising this flag was part of daily temple rituals.

Therefore, the pillar’s primary identity was religious. It was an integral part of a Vishnu temple complex, marking the site as sacred territory and a place where the divine connects with the earthly realm.

Symbol of the king’s power and divine association.

The dhvaja-stambha also had a profound political meaning. By erecting it, King Chandra was making a dual statement:

Divine Legitimization: It proclaimed that the king’s rule was sanctioned by Vishnu himself. His military victories (“crossing the seven mouths of the Indus”) were not just his own achievements but were won with the grace of the god. This connected the king’s power to a higher, unchallengeable authority.

Imperial Authority: A victory pillar of such scale and permanence was a bold declaration of power. It was a permanent, unmissable announcement of the king’s conquests, his control over vast resources (to commission such a marvel), and his role as the supreme patron of faith. It was a symbol of his digvijaya (conquest of the quarters) and his status as a chakravartin (universal ruler).

In essence, the dhvaja-stambha was the physical point where divine power and royal authority met and reinforced each other.

B. Later Interpretations and Folklore

Over the centuries, as memory of its original purpose faded, the pillar became the subject of new stories and beliefs.

The Iltutmish legend: Not moved by the Sultan.

A common myth suggests that Sultan Iltutmish (1211-1236 CE), the ruler after Qutb-ud-din Aibak, moved the pillar to Delhi after a successful raid on Central India.

Why it’s a legend: This is highly improbable. The Qutub Complex was built by Aibak in 1192 CE, and the pillar is already mentioned in accounts from that time. It was already in Delhi when Iltutmish came to power. Historians believe it was moved centuries earlier, likely by the Tomar or Chauhan Rajput kings who ruled Delhi before the Sultans, to glorify their own capital.

Purpose of the legend: This story served to aggrandize the Sultans, portraying them as powerful enough to uproot and transport such a massive symbol of a defeated Hindu king.

Popular belief: Bringing one’s hands together around the pillar grants a wish.

The most enduring modern folklore is the belief that if you can stand with your back to the pillar and encircle it with your arms, your wish will be granted.

Origin: This belief is likely a modern, playful twist on the pillar’s ancient aura of sacred power. People see its miraculous rust-resistant quality and attribute other miraculous powers to it.

The Challenge: The government has now erected a protective fence around the pillar, but before that, countless visitors attempted this feat. The real challenge isn’t supernatural; it’s physical—the pillar’s diameter is too large for most people to reach around. This very difficult added to the myth, as succeeding was a rare event and could be attributed to the pillar’s “blessing.”

This folklore shows how the pillar transitioned from a royal and religious symbol to a popular cultural icon of wonder and magic.

C. Its Recontextualization in the Indo-Islamic Landscape

The placement of the pillar within the mosque complex is one of the most fascinating examples of how symbols are repurposed in history.

Placement within the Quwwat-ul-Islam Mosque complex.

When Qutb-ud-din Aibak began constructing the Quwwat-ul-Islam (“Might of Islam”) Mosque around 1192 CE, he did not destroy the pre-existing pillar. Instead, he intentionally incorporated it into the courtyard of his new mosque.

It was placed directly opposite the prayer hall (qibla wall), making it a central focal point.

This was a common practice; the mosque itself was built using materials (columns, pillars) from 27 demolished Hindu and Jain temples. The Iron Pillar was the grandest such “spolia” (reused building material).

Transformation from a Vishnu-Dhvaja to a part of a new architectural narrative.

This act of incorporation was deeply symbolic and politically astute:

Symbol of Conquest: By placing the victory pillar of a great Hindu emperor at the heart of his mosque, the Sultan was sending a clear message. He was demonstrating the triumph of Islam over the indigenous religions and the subjugation of their former rulers. The might of Chandragupta was now contained within, and superseded by, the “Might of Islam.”

Claiming Legacy: It was also a way for the new Sultans to ground their rule in the subcontinent’s history. By appropriating this ancient symbol of power, they were inserting themselves into the lineage of great Indian emperors, suggesting a transfer of authority and legitimacy from the Guptas to themselves.

Thus, the pillar’s meaning was completely transformed. From a Vishnu-Dhvaja marking a sacred Hindu space, it became Allah’s Minaret (as some later called it), a war trophy symbolizing the establishment of a new political and religious order in India. Its continued presence tells a layered story of power, faith, and cultural change.

Comparative Analysis

A. Comparison with other Ashokan Pillars (e.g., Sarnath, Lauriya Nandangarh)

While both the Ashokan Pillars and the Mehrauli Iron Pillar are iconic free-standing pillars, they are vastly different in almost every aspect, representing two distinct eras and purposes.

| Feature | Ashokan Pillars (c. 3rd Century BCE) | Mehrauli Iron Pillar (c. 4th-5th Century CE) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Purpose: Edicts vs. Commemoration. | Propagative and Administrative. Their primary purpose was to spread the moral and ethical edicts (dhamma) of Emperor Ashoka. They were proclamations inscribed with rules for good governance, non-violence, and social harmony, meant to be read by the public. They were tools for communication and governance. | Commemorative and Religious. Its purpose was to commemorate the victories of a king (Chandragupta II) and to serve as a sacred religious object (a dhvaja-stambha or flagstaff) dedicated to Lord Vishnu. It was a symbol of royal glory and divine patronage, not a public notice. |

| 2. Material: Sandstone vs. Wrought Iron. | Chunar Sandstone. These pillars are made of finely chiseled stone, specifically a bright, buff-colored sandstone quarried in Chunar, near Varanasi. The stone was chosen for its ability to be polished to a brilliant shine. | Wrought Iron. The pillar is made of forged metal, not carved stone. It is a testament to metallurgical skill rather than stone-carving artistry. Its material is its most defining and mysterious feature. |

| 3. Craftsmanship. | Exquisite Stone Carving and Polish. The craftsmanship is defined by their architectural perfection. They are monolithic (carved from a single piece of stone), display a legendary mirror-like polish, and are topped with elaborate, realistic animal sculptures (like the Lions of Sarnath, which became India’s national emblem). The focus is on sculptural beauty. | Monumental Blacksmithing and Forging. The craftsmanship here is in the field of metallurgy. The skill lies in smelting, forging, and hammer-welding over 6 tonnes of iron into a single, cohesive object without modern technology. The capital (the top part) is a simple, stylized bell shape, lacking the intricate sculpture of Ashokan pillars. The focus is on engineering prowess. |

In Summary: Ashoka’s pillars are masterpieces of stone carving and political messaging from the Mauryan era. The Mehrauli pillar is a masterpiece of metallurgical engineering and royal glorification from the Gupta era.

B. Other Contemporary Iron Objects in India (e.g., iron pillars in Dhar, Mandu, Mount Abu)

The Mehrauli pillar is not entirely unique; it is the finest example of a tradition of large-scale iron working in ancient India. Comparing it to others highlights just how exceptional it is.

The Iron Pillar of Dhar (Madhya Pradesh)

Description: Now lying broken into three pieces, this pillar was originally estimated to be over 13 meters (43 feet) tall—almost twice the height of the Mehrauli pillar. It was erected by King Bhoja of the Paramara dynasty in the 11th century CE.

Comparison: It was clearly an attempt to emulate the Mehrauli pillar’s grandeur. However, it could not replicate its metallurgical success. The Dhar pillar is heavily corroded and eventually fell, likely due to flaws in its forging or less optimal chemical composition. This failure underscores the superior and perhaps lost advanced technique of the Gupta ironsmiths.

The Iron Pillar of Kodachadri (Karnataka)

Description: A smaller, 12-foot tall iron pillar located near a temple on the Kodachadri hill.

Comparison: Its purpose is less clear, though it’s also likely a victory pillar or a religious symbol. Its smaller size and less famous status highlight that creating a massive, corrosion-resistant pillar like the one in Mehrauli was a rare, resource-intensive project that only the most powerful empires could undertake.

The Iron Beam at the Konark Sun Temple (Odisha)

Description: A large iron beam used in the 13th-century CE construction of the Sun Temple to stabilize the structure.

Comparison: This shows that the use of large wrought iron elements in architecture was a known practice. While not a free-standing pillar, it demonstrates that the knowledge of forging large iron pieces persisted for centuries after the Gupta period, though again, without the same legendary rust-resistant properties.

The Iron Pillars at Mount Abu (Delhi Sultanate period)

Description: Two smaller iron pillars supporting a mandapam in the Dilwara Jain Temples complex.

Comparison: These are structural elements, not commemorative monuments. They show the continued use of iron in religious architecture but on a different scale and for a different purpose (functional support vs. symbolic celebration).

Conclusion of Comparison: The existence of these other iron objects confirms that the Mehrauli pillar was part of a broader technological culture. However, its exceptional size, flawless construction, and unparalleled corrosion resistance set it apart. It remains the undisputed pinnacle of this ancient tradition, a feat that subsequent generations admired but could not fully duplicate. Its survival intact for over 1600 years is what makes it a singular marvel in the entire world.

Conclusion: The Pillar’s Legacy

A. Summary of its multifaceted importance

The Mehrauli Iron Pillar is not a relic with a single story; it is a palimpsest of Indian history, with each layer offering a different kind of significance.

Historical Importance: It is a direct, tangible link to the Gupta Empire, the “Golden Age” of ancient India. It anchors the glorious era of Chandragupta II Vikramaditya in physical reality, providing evidence of the empire’s vast geographical reach, immense resources, and ambition for grand imperial projects.

Epigraphic Importance: The inscription is a primary source document carved in metal. It is a poetic prashasti (eulogy) that offers invaluable data on the political ideology of the Guptas, their military campaigns, and their system of religious patronage. It moves our understanding of Chandragupta II from the realm of legend into documented history.

Metallurgical Importance: This is the pillar’s most celebrated aspect. It stands as a testament to ancient India’s advanced scientific and technological knowledge. Its rust-resistant nature, achieved through a unique chemical composition and forging process, was a feat of engineering that was not surpassed for centuries. It symbolizes a deep, empirical understanding of materials science.

Symbolic Importance: The pillar’s meaning has evolved over time. Initially, it was a dhvaja-stambha—a symbol of divine connection and royal power for a Hindu king. Later, it was repurposed as a trophy of conquest within a mosque, symbolizing the triumph of a new Islamic order. Today, it stands as a symbol of India’s enduring and resilient civilizational identity, having witnessed and withstood the passage of time and changing political powers.

B. Its status as a national treasure and a symbol of India’s ancient scientific prowess

The Mehrauli Iron Pillar is universally recognized as a national treasure and is a protected monument of national importance by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI). Its image is iconic, instantly recognizable to millions of Indians.

More specifically, it has become a powerful symbol of India’s ancient scientific and technological prowess. In a world often unaware of India’s contributions to science beyond mathematics and philosophy, the pillar is a silent, undeniable witness to a sophisticated industrial past. It is:

A benchmark in the history of metallurgy, studied by scientists and historians from around the world.

A point of national pride, demonstrating that ancient Indian craftsmen and engineers achieved a level of skill that continues to inspire awe and curiosity.

An inspiration for future generations, proving that innovation and excellence are deep-rooted in the Indian subcontinent’s history.

C. Acknowledgment of ongoing research and unresolved questions

Despite being studied for over a century, the pillar still holds mysteries that fuel ongoing research.

The Exact Original Location: While the evidence strongly points to Udayagiri, the debate is not entirely settled. Are there archaeological clues yet to be found that could conclusively prove its original site?

The precise “recipe” and process: While the broad reasons for its corrosion resistance are understood, the exact smelting and forging techniques used by the Gupta ironsmiths are not fully replicated. How did they achieve such a uniform weld and consistent composition throughout such a massive object with the technology available at the time?

The full timeline of its move: We know it was likely moved by the Tomars or Chauhans, but exactly when, by which king, and by what engineering method was a 6-tonne pillar transported over hundreds of kilometers? The details of this logistical feat are lost to history.

Long-term conservation: Ongoing scientific research also focuses on its preservation. How is the modern, more polluted environment of Delhi affecting the stable passive layer? Scientists continuously monitor the pillar to ensure this ancient marvel is protected for future generations.

In conclusion, the Mehrauli Iron Pillar is a timeless bridge connecting India’s glorious past to its present. It is a historian’s document, a scientist’s enigma, and a nation’s pride, all forged into one enduring iron wonder.

Potential Questions/Topics for Discussion:

- The Mehrauli Iron Pillar is not merely an archaeological artifact but a mirror to the technological prowess of the Gupta period. Discuss.

- Critically analyse the inscription of the Mehrauli Iron Pillar as a source of history for the Gupta Empire.

- The rust-resistant nature of the Mehrauli Iron Pillar is a testament to the sophisticated knowledge of metallurgy in ancient India. Elucidate.

- What does the Mehrauli Iron Pillar tell us about the political ideology and religious patronage of the Guptas?

- Trace the journey of the Mehrauli Iron Pillar from a Vishnu-Dhvaja to its current location in the Qutub complex. What does this transition signify?

the notes are very useful for exams so thank you for this but the diameter of iron pillar is wrong i think because in google it is 41 cm and you shows 48 cm . But the notes are really helpful !

Thank you for your feedback! I’m happy the notes helped with your exams. I appreciate you mentioning the mistake about the iron pillar’s diameter. I’ll check the source and update the information to make sure it’s correct. Thanks again for being so detail-oriented!